We use cookies to improve your online experiences. To learn more and choose your cookies options, please refer to our cookie policy.

Join Dover Court this January!

Limited places still available in select year groups - Enquire Today

I can, like many of you, remember life before the internet. As a teenager, I found excitement in the painstaking process of dialling through a landline, listening to the sound of what felt like alien eavesdroppers, and exchanging a few messages with a friend over the course of 30 minutes! My students often find this hard to believe, and looking back, it does feel like a different world. Now, in just a matter of seconds, we can access information on any topic we’re curious about or watch expert demonstrations in high-quality video, complete with subtitles and the option to adjust the playback speed. And that’s not even considering the capabilities of large language artificial intelligence models that can serve as personal assistants in our learning endeavours! The capability to learn anything we want is now constantly at the fingertips of teenagers—or rather, the potential. In this article, I propose that self-regulated learning is the capability we should instil in our teenagers during this information age.

Self-Regulated Learning: More Than Metacognition

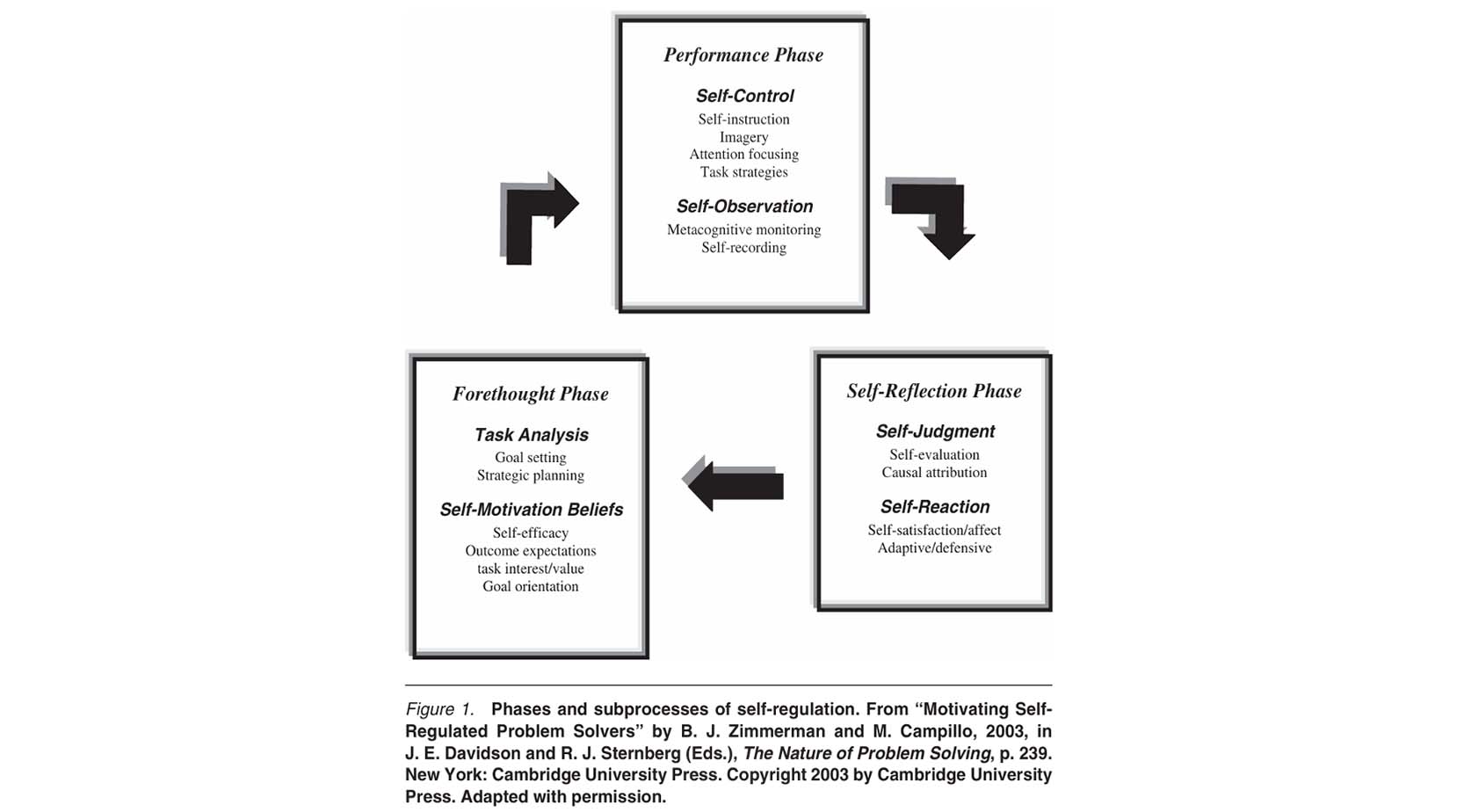

Metacognition is a fundamental skill in the learning process and has been a pedagogical focus for most of my career. I wrote an article detailing how I implement metacognitive strategies to support the development of Year 11 students at Dover Court International School (DCIS). However, there are additional important factors to consider. The American scholar Barry Zimmerman defined these students as “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviourally active participants in their own learning” (Zimmerman, 1990). I believe that many components of his three-phase cyclical framework, illustrated in Figure 1, will be somewhat familiar to you.

The Performance Phase focuses on the technical aspects of learning and is where metacognition occurs. Nord Anglia Education is supporting research initiatives to empower its educators to lead in pedagogical practices related to these processes. In February 2024, colleagues from 27 Nord Anglia schools began a large research project with Boston College to explore how to embed metacognition in their teaching effectively. In October 2024, they partnered with the Project Zero research centre at the Harvard Graduate School of Education to develop 18 Thinking Routines. Teachers across all Nord Anglia schools are implementing these routines in their classrooms to enhance students' metacognitive skills. Later this year at DCIS, I will collaborate with students on a research project focusing on the other phases of self-regulated learning as part of my master’s studies at King’s College London.

As you may know, modern professionals are expected to adapt throughout their careers, as roles come with shifting expectations that can only be met through ongoing professional learning. Last October, I introduced the idea of self-development as a superpower to Key Stage 4 students in an assembly. I explained this through two key concepts. Self-regulated learning can be considered the academic manifestation of this process, and it can be embraced in everyday life by adhering to these concepts.

A Growth Mindset Combined with Atomic Habits for Unlimited Self-Development

Firstly, I discussed the importance of a Growth Mindset, a concept propagated in educational circles through Mindset (2006) by Carol Dweck. A Growth Mindset differs from a fixed mindset; it is the belief that an individual's potential is not limited and can be developed across all areas of performance. This mindset operates within the Forethought Phase and highlights the significant impact our mindset has on motivation and subsequent performance. We should be mindful of using limiting language and instead harness the power of yet when discussing our development. For example, instead of saying, "I cannot do a handstand," we should say, "I cannot do a handstand yet." Richardson and colleagues (2012) conducted an extensive meta-analysis of academic literature, concluding that out of 50 factors, self-efficacy was the strongest predictor of academic success among college students. Self-efficacy refers to an individual's belief in their capability to achieve a specific outcome. However, a key challenge in building self-efficacy is that it is rooted in personal belief; therefore, agency and responsibility are crucial components for development.

The second concept is based on James Clear's popular Atomic Habits (2018), which focuses on behaviour. Clear emphasises the importance of implementing systems for improvement rather than solely focusing on goals for change. He highlights the importance of habit formation in maintenance and utilises the analogy of compound interest for its power in long-term accumulation. This approach includes a Self-Reflection Phase, as it requires us to view the impact of routines to refine them. One particularly powerful takeaway from Clear’s philosophy is the advice to identify what you can do on your worst day to maintain consistency with your habits. For example, a student planning to complete past-paper questions might settle for a 20-minute walk while recording a voice note to verbally review their knowledge on a topic. Habit formation embodies the cyclical nature of self-regulated learning, as shown in Figure 1, which outlines the essential approach for effective learning.

I believe that we can instil these concepts as frameworks for motivation and behaviour towards practising self-development. When these frameworks are in place, individuals can acquire metacognitive skills, completing the triad of essential factors for self-regulated learning. This, in turn, will enable young people to flourish in today's information age and prepare them for the demands of future careers. As I have increasingly discovered through my leisure activity of reading history, the ancient Greeks were likely aware of this concept. Aristotle summarised it well by stating, "We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit."

Mr. Matthew Tuckley

Year 11 Progress Leader

Further reading

Clear, J. (2018) Atomic Habits. New York: Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset. New York: Ballantine Books.

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological Correlates of University Students’ Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: An Overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3–17.