A brief history of vaccines and learning through a STEAM investigation

Vaccines have shown to be crucial to the fight against diseases in the history of medicine. Throughout history, they have helped to significantly reduce the incidence of polio, measles and tetanus, among many other infections. Today, they are considered the most cost-effective strategy in the control of viral and bacterial diseases.

Vaccines have shown to be crucial to the fight against diseases in the history of medicine. Throughout history, they have helped to significantly reduce the incidence of polio, measles and tetanus, among many other infections. Today, they are considered the most cost-effective strategy in the control of viral and bacterial diseases.

Vaccines are biological substances introduced into people's bodies in order to protect them from disease. They activate the immune system, "teaching" our bodies to recognize and fight viruses and bacteria in future infections.

They are composed of agents similar to the microorganisms that cause diseases, toxins and components of these microorganisms, or the aggressor agent itself. In the latter case, there are attenuated (the weakened virus or bacteria) or inactive (the dead virus or bacteria) versions (Fiocruz, 2021).

When introduced into the body, the vaccine stimulates the human immune system to produce the antibodies necessary to prevent the disease from developing if the person comes into contact with the viruses or bacteria that cause it.

Vaccines have helped in the control of many outbreaks during the twentieth century. As an example, the measles vaccine, discovered in 1963, has dropped the number of cases over the last decades of the century and the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Measles cases over the two last decades of the twentieth century

(Source: World Health Organization)

In 1798 the term “vaccine” first appeared, thanks to the experiments of the English physician and scientist Edward Jenner. He heard reports that rural workers did not get smallpox, as they had already had cowpox, which had a milder impact on the human body. He then introduced the virus of cowpox into an eight-year-old boy. The result of this experiment showed that the child did not present the heavy symptoms of smallpox as he had been previously exposed to a virus that "taught" his immune system how to fight against the actual harmful virus. Consequently, Jenner realised that the rumor did indeed have a scientific basis. The word vaccine derived from "Variolae vaccinae", the scientific name given to cowpox.

At BCB, our secondary students have investigated how quickly a viral disease could spread through the classroom and "created" a pandemic through a simulation. This activity was part of "Save the World with STEAM'' ECA.

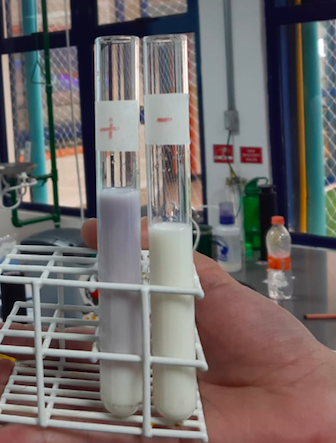

All students received test tubes containing milk, except one, who was given a mixture of milk and starch. This student represented the "infected" person, but no student knew who had the starchy milk test tube. Starch can be identified by mixing it with iodine solution. A gray colour shows a positive result for the presence of starch, as observed in the image below. The iodine test represented a PCR test in our investigation.

Test for starch: gray colour shows a positive result and white colour shows negative result

(milk present only)

Once all students had their test tubes, they were requested to collect a small amount of their liquids so that we could discover which student was the one that started the "virus" spread (in this case, the starch spread) at the end of the investigation. In each round of spread, they had to mix half of their remaining liquids with the liquid of another student, transferring the "virus" (starchy milk) to an unsuspecting victim, repeating this process five times.

Students mixing their samples

After each round, the students recorded the name of the person who they mixed their samples with in a table, so that they could trace their contacts later.

Students recording data

After the five rounds, all students' mixed samples were tested with iodine solution, showing that the outbreak had occurred due to the mixing of "healthy" samples of milk with "infected" ones, as most of them turned gray, showing that many students got "sick". By checking their results table, the students were able to trace their contacts so they could figure out the student who started the spreading of starch. Once they gathered some clues to design predictions, the final result was revealed through the test with their original samples that were not mixed before the rounds, as seen below.

Revealing the student who started the outbreak: Zoe from Y11!!!

To conclude the session, discussions about safety and ways to prevent new outbreaks were raised by the students, as well as the importance of vaccines in this historical moment we live in. With this investigation, students were able to think as a scientist and create hypotheses to solve the mystery of starch transmission. Students had a lot of fun and they were engaged to explore a problem, being placed at the centre of their own learning.